Exploring the Origins of The Italian Language – A conversation with Stony Brook University’s Dr. Fedi

By Silvia Davi

There is no question that the Italian language is one of the most beautiful and studied languages in the world. As someone that was raised in a multilingual home, I appreciate learning the origin of languages, and as a result, I have studied all Romance languages and even Modern Greek to help deepen my understanding of languages. I credit my parents for instilling the importance of studying languages, raising me in a multilingual home, and opening my eyes to be able to connect with my roots and other individuals. Furthermore, in addition to being raised speaking Italian, Spanish (and of course my native English), I am forever grateful to my parents for ensuring I treat the Sicilian dialect, like another language, which I spoke exclusively to my Nonna.

On the topic of the Italian language, I recently had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Andrea Fedi, Associate Professor of Italian and Cultural Studies Director of the Center for Italian Studies, which was founded in 1985 by Stony Brook University Distinguished Service Professor, Dr. Mario B. Mignone. The Center for Italian Studies was founded r to provide cultural enrichment that reflected the cultural heritage of the Italian and Italian American community on Long Island. For the last half century, the Center for Italian Studies at Stony Brook University has built a strong cultural bridge between the University and the community at large.

Born and raised in Pistoia, Tuscany, I explored some interesting facts about the Italian language with Dr. Fedi, providing clarity on the beautiful “lingua italiana” so often credited with Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy. Read below to learn more.

Q- What are some interesting facts about the Italian language?

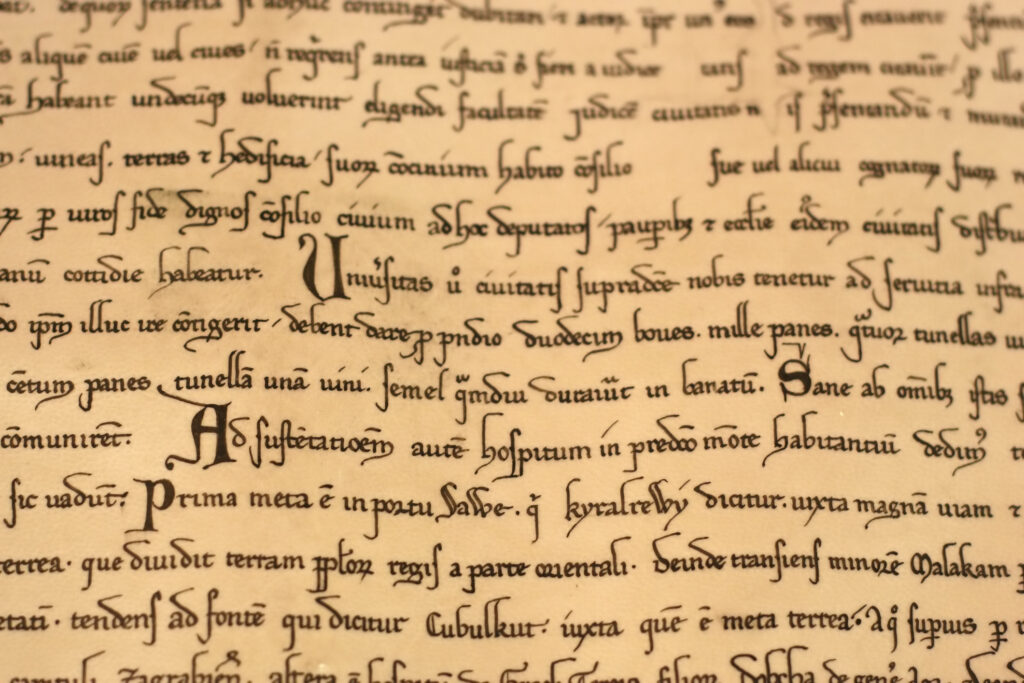

Multiple vernacular languages evolved from Latin, but the Florentine and Tuscan variants emerged as the chief instrument for inter-regional communication, particularly in commerce, largely due to Florence’s economic power and its gold currency, the florin. While Latin remained the language of academia, diplomacy, and law, the literary masterpieces of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio elevated a refined version of Florentine dialect to serve as the foundation for a national language long before political unification even started.

It is said that the Italian language was taken from the Tuscan dialect after Dante Alighieri wrote the La Divina Commedia / The Divine Comedy. Can you tell us more about that?

While it’s a popular simplification to say that Italian comes directly from Dante’s Divine Comedy, the reality is much more complex. Dante’s groundbreaking choice to write a text grounded in philosophy and theology in Florentine rather than Latin was revolutionary, but equally significant was his theoretical defense of vernacular language in De Vulgari Eloquentia. Still, the process of language standardization also involved other key figures like Petrarch and Boccaccio, and later the systematic work of Pietro Bembo in the 16th century. Finally, Manzoni’s model, combining traditional models with the Florentine spoken during his time, had a big influence on the linguistic standards set by the governments when the Italian kingdom was established and they had to decide what to teach in the national schools.

What are some misconceptions about the Italian language and its dialects that you would like to clarify?

A common misconception is that Italian dialects are simply variations or corrupted forms of standard Italian. In reality, Italian dialects are distinct languages that evolved parallel to Florentine from Latin, each with its own vocabulary, grammar, and phonological system. Another misconception is that these dialects are spoken only by uneducated people or the elderly. In fact, many Italians regularly switch between their local dialect and standard Italian depending on the social context, a practice known as diglossia. Finally, while standard Italian emerged from Florentine, this doesn’t mean Florentine was inherently superior to other vernaculars — its prominence was largely due to economic and cultural factors.

You are from a historic city in Tuscany called Pistoia, tell us about what it’s best known for.

Pistoia has roots stretching back to Roman times, with legends connecting its population to the survivors of Catiline’s rebellion against Rome. The city’s questionable reputation is immortalized in Dante’s Inferno through the character of Vanni Fucci, a notorious thief who stole from Pistoia’s Cathedral, and in Machiavelli’s The Prince, where Pistoia’s feuds are used as an example to invoke the use of cruelty to stop internal divisions. The city’s factional struggles had a far-reaching influence: the second American President, John Adams studied the history of Pistoia as he was afraid that similar feuds could negatively affect the union. Today, while preserving its rich historical heritage in its stunning Piazza del Duomo, Pistoia is internationally recognized for its thriving plant and flower nursery industry.

What are some of your favorite Renaissance works of art and why?

I’m particularly drawn to Benozzo Gozzoli’s fresco cycle of the Life of Saint Augustine in Sant’Agostino Church in San Gimignano. Gozzoli depicts Augustine not just as a saint, but as a human being moving through various life stages — from his early education in Carthage to his spiritual transformation in Milan. What makes these frescoes especially striking is their detailed representation of 15th-century social life, architecture, and customs, with Gozzoli using the faces of his contemporaries as models, essentially translating Augustine’s late imperial biography into the visual language of Renaissance Tuscany.

Tell us about the Center of Italian-American Studies at Stony Brook University. What is the goal?

The Center for Italian Studies, established at Stony Brook University in 1985 under the leadership of Dr. Mario Mignone, represents a significant bridge between academia and the Italian-American community. Through Dr. Mignone’s vision and community engagement, the Center secured funding to establish the prestigious D’Amato Chair in Italian and Italian American Studies. The Center’s mission extends beyond traditional academics, actively preserving and promoting Italian and Italian-American heritage through multiple channels: scholarly lectures and conferences, language programs for both children and adults, and academic support through fellowships and scholarships. These scholarships specifically support students pursuing Italian studies or preparing to become Italian language educators, ensuring the continuation of Italian cultural education for future generations.

Silvia Davi

Founder, Host & Contributor

Renaissance Minds

mobile:+917-836-9957

email: RenMindsPress@gmail.com

instagram: @renaissance_minds

info: Website/Blog